Common Good and the Border

- London Catholic Worker

- Sep 28, 2025

- 5 min read

Community member Thomas Frost writes on his experience volunteering in the Maria Skobtsova House in Calais.

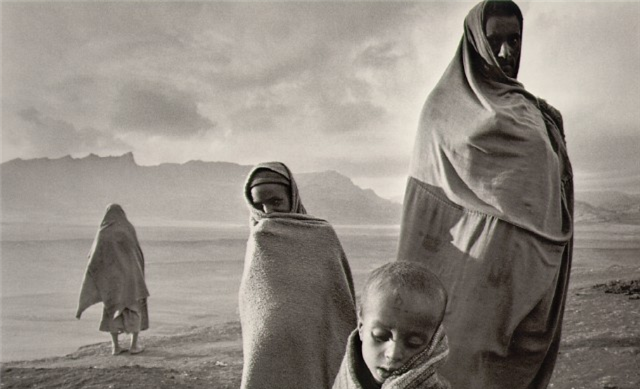

What surprised me most about Calais was how ordinary it was. You could easily spend a week or two there as a tourist, as people often do, and have no idea that it is the site of a humanitarian catastrophe caused by the brutal British-French operation, costing hundreds of millions of pounds, to prevent migration across the Channel. Great effort has been spent keeping migrants, and violence against migrants, out of sight. The proliferation of walls topped with barbed wire, and former public parks filled with boulders to prevent the pitching of tents, would not speak of the tear-gassing of children, of their being fired at with rubber bullets, of masked police sinking boats filled with terrified people by slashing them open with knives, or of the denial of medical treatment for injuries to those who didn’t already know about them. The authorities have decided that, for the sake of the common good in their countries, migrants have to be treated as though they were not human beings, and so, to avoid offending those who would see them as humans, they keep their practices largely hidden.

Even within political movements advocating for migrants there exists a tendency to overlook the dignity of some people for reasons of pragmatism. Most people in this country will still acknowledge that we have some collective responsibility to “genuine refugees,” so it is tempting to focus exclusively on the stories of those we might expect to be regarded as “genuine”—often children and those fleeing relatively well-publicised warzones—in the hope of convincing as many people as possible that some change of policy is required. A focus has been on the creation of limited “safe, legal routes” for at least some people to claim asylum without making the dangerous crossing. While the existence of such routes would be an improvement on the situation as it stands, they will fail to solve the problem just to the extent that they are limited.

Those excluded will continue to take dangerous routes, or remain in intolerable situations from fear of violence. The Refugee Council, against the overwhelming majority of groups working directly with migrants, supported August’s “one in, one out” deal between France and Britain on the basis that it would create an extremely limited route of this sort. Since under the deal equal numbers of migrants would be forcibly expelled to France, we might consider exactly what judgments need to be made about the dignity of the deal’s victims and the value of their interests for it to be regarded as supportable.

Christianity should provide a model for political thinking. Attention has to be continuously redirected towards the more marginalised and most easily ignored if we are to have a politics which genuinely reflects human dignity, and to think about the Cross should always be to think of these groups. Unfortunately, Catholic thinking on borders and migration has become very confused. If you are unwise enough to search the internet for the Church’s teaching on the matter, you will find a series of articles referring to paragraph 2241 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC), which, after it refers to the obligation of wealthy countries to welcome foreigners in search of security (including economic security), states that political authorities may restrict the exercise of the right to migrate “for the sake of the common good to which they are responsible”. Even publications more sympathetic to migrants have taken this as a general authorisation for the illegalisation of migration whenever it might adversely affect the social or economic situation of the receiving country. More alarmingly, J. D. Vance has cited it to justify the spectacle of cruelty currently being carried out under the name of immigration enforcement by his government which, unlike most of its European counterparts, no longer feels a need to conceal its brutality. These being the stakes, it is worth thinking carefully about what the “common good” really involves.

The CCC itself refers, as it generally does when discussing political community, to Gaudium et Spes (GS), which defines it as “the sum of those conditions of social life which allow social groups and their individual members relatively thorough and ready access to their own fulfilment”. GS refers to the need, in an increasingly interconnected world, for governments to consider a universal common good as well as a common good within their own communities, an idea taken forward by Pope Francis in Fratelli Tutti. But even leaving that aside, while the provision of basic needs such as food, shelter, and clothing are necessary for human fulfilment, they do not constitute it in themselves. Human fulfilment, ultimately, is to know and love God; this is the end for which Christians believe we are made. And to know and love God is to know and love him in his creation, and particularly in other people. GS goes on to identify the perfection of human community in the Church, a community defined by the self-giving love of its members towards one another (GS 32). If, therefore, political authority derives its legitimacy from its contribution to the “common good” (GS 74), which is the creation of conditions in which human fulfilment is made most possible, the proper role of any political institution is not dissimilar to Peter Maurin’s mandate to “make the kind of society where it is easier for people to be good”.

Consequently, the idea that a border policy based on exclusion, let alone one based on brutal violence, could be a means of promoting the common good of its members is incoherent.

Our faith obliges us “to make ourselves the neighbour of every person without exception,” and “everyone must consider his every neighbour without exception as another self” (GS 27). We do not need to count up exactly how many people we are willing to let drown or starve to sustain the GDP, or preserve social cohesion, or win political concessions from right-wing governments, because as soon as we have decided to sacrifice some people for political ends we have lost the only legitimate basis for politics, which is to love all of our neighbours without exception. If we take our responsibilities seriously, we cannot accept any of the violence of the border, in its practice or its effect as a threat. Whatever life is left in our culture or political institutions will be destroyed by the very means that are being employed in a misguided attempt to save it. We will not save our country by turning it into a fortress surrounded by walls topped with barbed wire. We will be left with no country at all.