Fare Forward, Voyagers!

- Henrietta Cullinan

- Aug 10, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 15, 2024

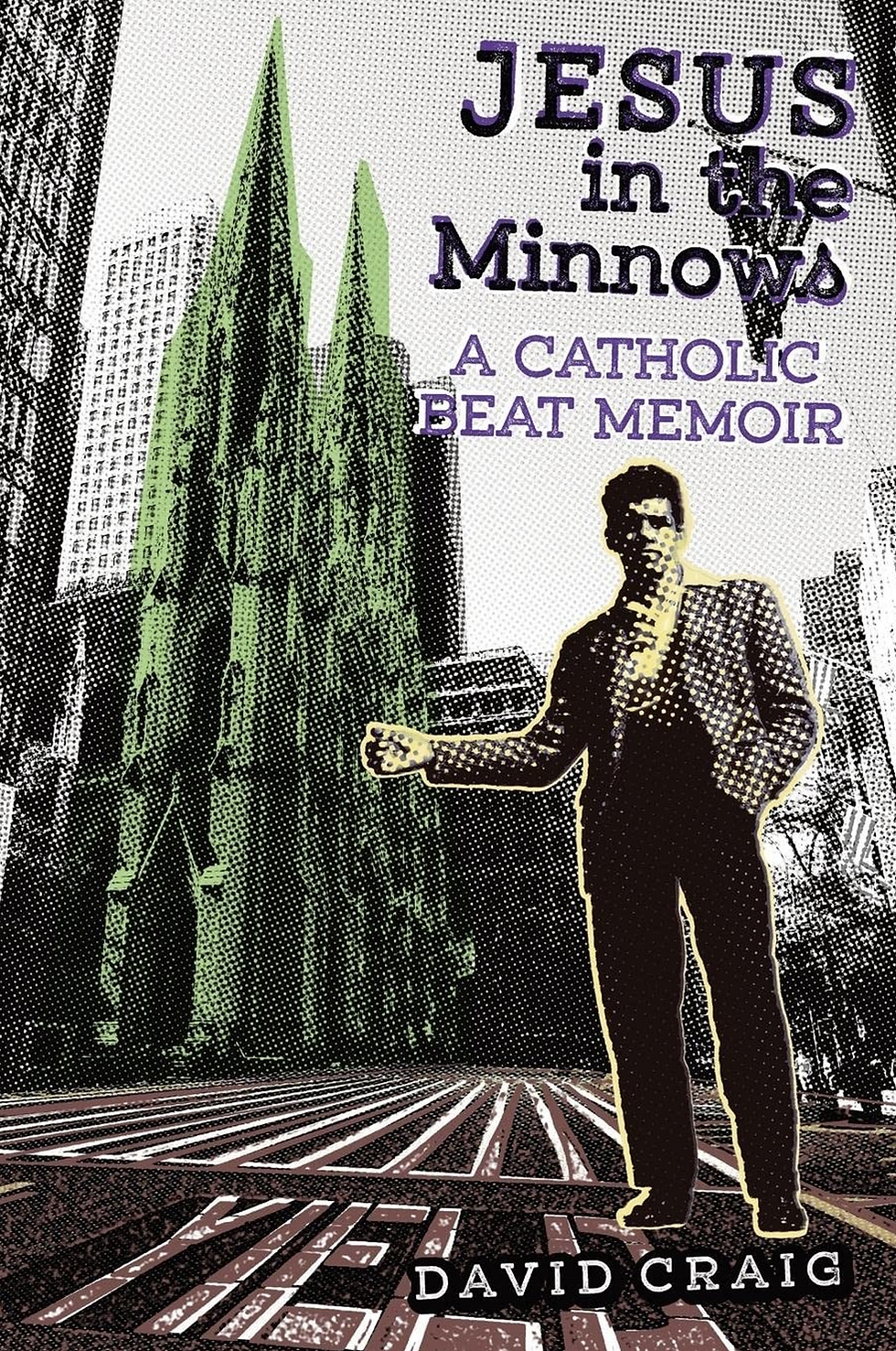

In this book, David Craig, real life poetry professor, becomes James, self-styled beatnik and narrator, in order to tell the story of his young adulthood. The book opens with the narrator walking out of his job and driving through the night, his girlfriend barely conscious in the back of the truck, across Ohio to Cleveland, where they plan to set up new lives. The ensuing tale reads as a life of drifting, of spontaneously taken journeys, by pick up, greyhound bus and hitch hiking.

For me, it reads as an account of poustinia, in the sense of setting out on a journey “with just a loaf of bread and a small sack of salt” to search for a place to settle, a community to serve.

A bit like Thoreau in ‘Walden’, James doesn’t spend much time in the actual poustinia, in this case at Madonna House, a religious community in Canada. All the same his time there, framed before and after by road trips, low paid jobs, spartan accommodation, tentative relationships, weed and mushrooms, carries the weight of the narrative. We anticipate it beforehand and wonder about its legacy afterwards. The process that led him there is shadowy but soon enough we find James alighting a bus in a small town, snow still piled up by the road, without a proper coat or hat, not sure what to do next. Having arrived, he is not sure how to behave. He maintains his diffidence and humour, but his jokes are received with blank stares. There are not many chances to meet girls; male residents are bused out every evening to a house away from the main compound. He wonders why people look so happy with so little on offer in the way of entertainment.

Ekaterina, nicknamed “Bee”, the founder of Madonna House, appears as “a large woman, of peasant stock it looked like in her loose-fitting cream-coloured shift.” Despite his misgivings, he joins the whole community to hear her lectures, “the least he could do” in return for their hospitality. She says, “Become poorer because you are beggars at the door of God.” And “I look around here and all I see are rich people in borrowed clothes”. He feels as if the words are directed at him, “The nerve”.

James spends his days sorting rubbish and donations and chopping wood, “frozen with boredom” until he eventually receives permission to spend a few days in one of the community’s poustinias.

Wanting to understand more, I turned to Catherine de Huek Doherty, the Ekaterina of this account, to read her own words on bringing the Russian concept of poustinia to the West, similar to the ones she visited in Russia with her mother. Poustinia literally means desert, a search for solitude, devotion to the people of a village community, a simple dwelling, with allusions to the desert fathers. A poustinik is someone who has been given permission to live in search of God, usually a man in their 30s or 40s, sometimes an older woman. Some spend a short time, a few weeks or a year, others their whole life in poustinia.

Finding an abandoned farmhouse nearby she sets it up as a poustinia for the Madonna House community, writing a wonderful, inspiring letter of explanation to her supporters. She is very specific: bread and water or tea and coffee for westerners, simple furniture, no books except a bible. The idea turns out to be very popular.

She later responds to some unease within the community and decides to found a poustinia in an urban setting. This poustinia, “not for amateurs” is now in the heart. The modern day poustiniks will go about their business, just as a pregnant woman goes about her duties, with new life growing inside her. “You are pregnant with Christ” she says.

James experiences conversion, then disappointment. Ekaterina says to him, “So you’re ready to change the world now, hey, honeymooner” then prophetically “But now you must climb the cross…”

James leaves Madonna House, and hitches to Denver. On the way he punches a fellow hitch hiker who asks him, “Are you saved?” When work in the construction industry dries up, he becomes a taxi driver. He describes his fares, his boss and his landlord, quoting Ginsberg, “my wagon full of sunflowers”. A strong feature of this book is his devotion to the large cast of assembled all sorts, the “minnows” of the title: workmates, bosses, landlords, friends of friends, fellow hitchhikers, ones who offer hospitality, who appear in chance encounters, who often turn out to be poets. Helping the prose along is the narrator’s education in poetry. Indirect quotations from T.S. Eliot (Fare forward, voyagers!), Johnny Cash, Jack Kerouac, Kavanagh, Berrigan, Thich Nhat Hanh give the story its place within the Beat generation, coupled with deep appreciation for humanity. Thanks to the author’s determination not to be pious or judgemental, I found this a gentle, consoling, easy-going text, despite the tough subject matter, including drug taking and patronising attitudes to women.

In the final chapter, decades have passed. We learn some new things about James, that he still drives a cab, that he is half Choctaw Indian, that both he and his partner have suffered from childhood trauma which has effected their whole family. Although he recounts personal struggles with an evil spirit, a desire for fame for instance, he implies but does not recount the struggles of family, children, marriage, professional disappointment, that follow this tale, instead ending with the single word “Mercy”.

According to de Hueck Doherty, there’s a demand, in the life of the poustinik, to give up his solitary search for God and help the villagers with the haymaking or harvest whenever it’s needed. As Ekaterina tells “James”, “Don’t worry... you’ll find the words.”